This sermon continues a series on the principles of the Unitarian Universalist Association. Last month we talked about our first principle— the inherent worth and dignity of every person; today we’ll talk about the second principle e of Justice, Equity and Compassion in Human Relations.

UUA – second principle Justice, Equity and Compassion in Human Relations

Interestingly, there is a reason behind the order of the principles. The intention of the committee that formulated them in the 1980s was to go from the individual to the expanding context of community, world, and universe. (Edward Frost, With Purpose and Principle, p. 20) So the second principle takes us from the inherent worth and dignity of each individual to the realm of human relations, and how we want to be in relationship with others. My colleague Anne Treadwell says, “The second principle follows from the first, I think. It’s because we affirm the inherent worth and dignity of every person that we commit ourselves, as congregations and individuals, to work for justice, equity, and compassion. If we thought that some groups of people were without inherent worth, were disposable in fact, there wouldn’t be much incentive to work for those values which suggest fair and equal treatment for everyone.”

I talked about how the first principle is essentially a theological statement. With the second principle, we put some muscle on those theological bones. UU minister, Tom Owen-Towle describes Unitarian Universalists as “freethinking mystics with hands.” The second principle is about those hands.

Like the first principle, this one seems pretty easy at first. After all, who isn’t for justice, equity and compassion? How could it possibly be difficult to affirm and promote that? But like the first principle, once we start to examine what it entails, we see just how much this second principle really asks of us.

Deeds Not Creeds

We Unitarian Universalists talk a lot about what we believe – or what we don’t believe. We talk a lot about our different theologies, our diversity of beliefs. But what defines us as Unitarian Universalists is not anything to do with belief, but how we act in the world. Our actions define us precisely because we don’t have a creed. “Deeds not Creeds!” has been a favorite UU motto.

Usually, this is articulated as a concern for justice. As the Rev. Linda Hoddy says, “We UUs are concerned with justice. We are known for our social justice work. There are reasons for that in our theology. Many UUs do not subscribe to literal heaven to which we will all depart after death. Thus we have always emphasized that a heaven is a place we must create here on earth, here and now. The kingdom of God, or the kingdom of heaven, of which Jesus spoke so much, is something we believe we must create here. Not liking hierarchical images very much, we might be more likely to speak of “creating the beloved community”, rather than the kingdom of heaven. We don’t have much faith in heaven after death. So, values like “justice” and “equity” and “compassion” require incarnation in this life, as we walk the earth.”

Justice. Equity. Compassion. A Unitarian Universalist trinity.

We are indeed known for our social justice work. We show up at rallies and protests and pride marches, often in our yellow “side with love” shirts. We participate in interfaith coalitions, partner with progressive organizations, and even lobby politicians. We work to get people out to vote, to feed the hungry and shelter the homeless. We are active in promoting reproductive rights, gender equity and rights for LGBTQ+ people. And of course, we are committed to working for justice for people of all races, economic status and ethnicity. We want to end oppression and White Supremacy, not only for people, but for the earth and all its inhabitants.

We have long been known for our justice work because throughout the history of both Unitarianism and Universalism, as well as the post-merger denomination, we have been in the forefront of justice and equity issues.

Abolitionists

Many of the most outspoken were Unitarians – Channing, Emerson, Parker, and other prominent Unitarians worked to eliminate slavery. In more recent times, we took part in large numbers in the Civil Rights movement. James Reeb, who is held up as a modern-day Unitarian Universalist martyr, was killed when he went to march at Selma. The story has been covered in the UU World, along with other stories of our history of anti-racism work. And we’re still at it.

Women’s Rights

We also have a long history of working for women’s rights. The suffrage movement included many of our forebears– in particular Unitarians Susan B. Anthony and Lucy Stone, and Universalist Olympia Brown. As a denomination, we have taken the lead in admitting women into ministry, achieving the distinction of reaching 50% female clergy about twenty years ago.

Gender Equality and Acceptance

We led the way in our work on sexual orientation and gender justice issues. Our ministers were officiating same-sex weddings long before they were recognized by governmental institutions. We were welcoming openly gay and lesbian clergy into our ranks long before other religious bodies were willing to admit them. We were in the forefront of efforts to confront oppression of this population, and had a large role in the ultimate national legalization of same-sex marriage.

In the last 10-20 years, we have finally been getting serious about working on issues of ecological justice. Our Green Sanctuary program is part of that. As climate change and species extinction have accelerated, the need to work on this has become more and more urgent.

There are so many more examples I could give, so many more ways Unitarians, Universalists, and Unitarian Universalists have been and are involved in justice efforts. And I bet you could give some too.

Dick Gilbert describes a New Yorker cartoon: “It shows three fish swimming, one behind the other. First is a small fish saying, “There is no justice.” Immediately behind, ready to swallow it, is a larger fish saying, “There is some justice in the world.” Finally, there is a larger fish about to swallow both saying, “The world is just.” (Sermon in Edward Frost, With Purpose and Principle, p. 38) But justice does not depend on your point of view—or in theory it should not. True justice looks the same to any point of view.

The philosopher John Rawls created an intriguing way to get at true justice by getting around any particular point of view. He imagines what he called the “original position,” a position of neutrality with no knowledge of our own position in life, so that, sitting behind a veil of ignorance about ourselves, we might create a social contract that is truly fair. UU minister Laurie Bilyeu summarizes Rawls’ theory well:

“Suppose we’ve found a way to recreate society. Imagine this with me. A new society is about to be formed. Our task is to create the social contract. What would be the rules, standards, agreements that would define a just society?

What would a world ruled by justice look like?

Everything is on the table. Every political boundary and system. Every form of social service and policy. Every attitude, every standard of success… We are making up the social contract, and we will participate in that new society, but we don’t know what role we will play or who we will be.

You might live in South Boston. Your skin might be black.

What must be included in the social contract for you to participate in justice?

You are a single parent.

You are a single parent with a special needs child.

Or perhaps you will be 85 years old and in need of much medical treatment and expensive medications.

What must be included in the social contract?

You are mentally ill.

You are unable to maintain a job.

What does justice look like to you?

You are madly in love with a person of the same gender. How must this new society function in order to include you?

You are a child in Kosovo, in East Timor, in Sierra Leone. How will you define justice?

You might find yourself living in Israel in this new society, or Northern Ireland, or Quebec, or Tijuana. What would the social contract have to look like to cause you to sign on not knowing who you will be in this society?”

This is a powerful way to think about justice. What do you think? Would this work? Could we create a just society if we came to the planning table not knowing what our role in that society would be?

Equality Versus Equity

And what about Equity? Webster says equity is “fairness or justice in the way people are treated.” It is often contrasted with equality, which distributes goods equally. Seeing justice as equality can actually be unfair.

An example is that in the past, some companies argued against providing maternity leave because benefits have to be equal for all employees, and they didn’t want to favor some employees with a nice benefit that others couldn’t get. I hope there aren’t any companies that do that anymore.

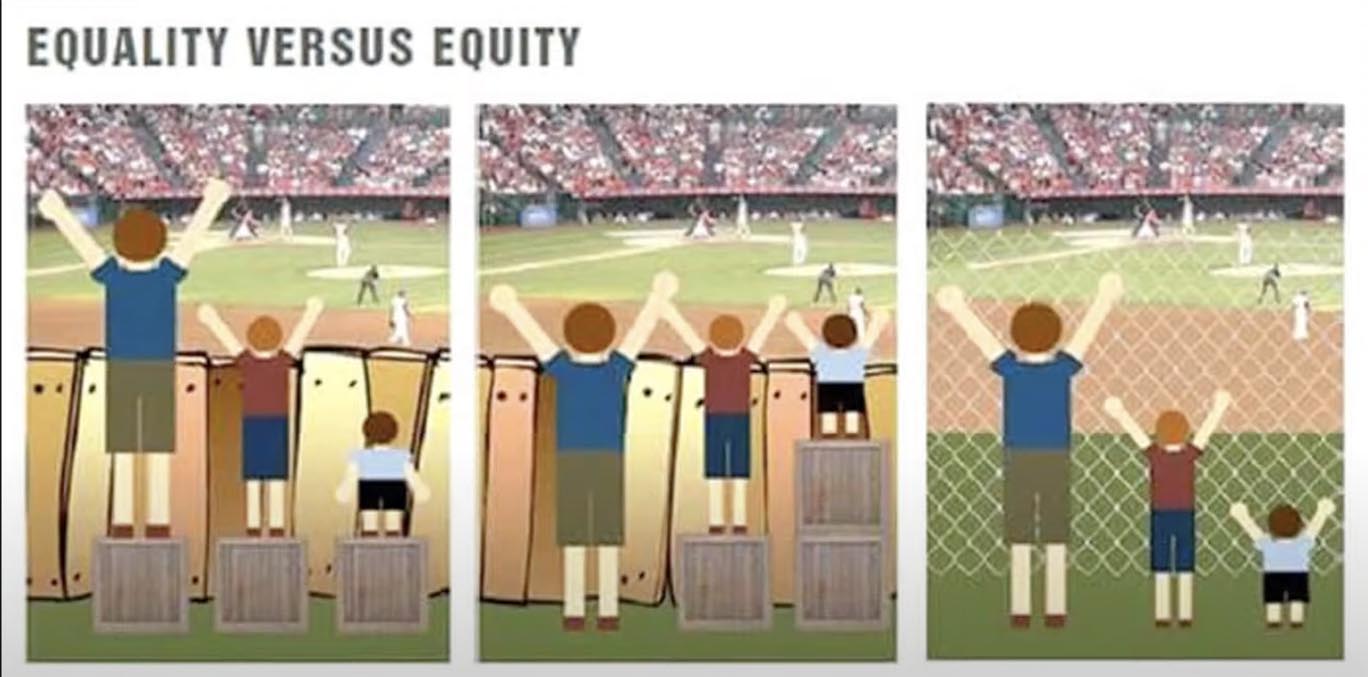

Equity goes a step further by giving people what they need and tailoring the distribution of benefits or goods to individuals or groups according to their different needs. In a sermon last year, I talked about this, and we shared the drawing of the children watching the ball game on the other side of a fence. The children have different heights, and so different abilities to see over the fence—or not, even standing on boxes. The graphic then depicts equity, which shows the boxes arranged so that everyone can see over the fence.

Equity is a special kind of justice. But there’s another kind of justice that goes even further—one where we eliminate the need to make special arrangements, where we make the playing field level, so to speak, by removing the barriers. In this case—changing the nature of the fence so that all can see through it no matter what their height.

As a review, equality is the equal sharing and division, keeping everyone at the same level. It gives the same thing to all people, regardless of their needs. A good example of equality is the opportunity for all children to attend public school.

Equity goes a step further. It means fair treatment, access, advancement and opportunity for all people. It strives to identify and eliminate barriers that prevent the full participation of some groups or individuals. Promoting equity requires an understanding of the causes of outcomes of disparities within our society. For example, adding a wheelchair ramp next to the steps at the public library aims for equity.

Justice

Justice, or social justice, is the view that everyone deserves to enjoy the same economic, political and social rights, regardless of race, socioeconomic status, gender and other characteristics.

As the illustration shows, justice requires us to remove some of the barriers that cause inequity. Another example of justice might be adding a field in an online form for our people to include their preferred name and gender identification. This respects their rights by not forcing them to identify according to societal norms, but rather by what is authentic to them.

Compassion

Compassion is what causes us to seek equity and justice. It is because we care that we want to reduce suffering and see that all are treated fairly.

The beauty contest winner cared about the blind man who needed help getting to the fairgrounds.

The woman in the reading felt compassion for the noodle thief, which led to her giving the other woman the lo mein in the to-go container.

Why are these concepts put together in this principle? Because Compassion and Justice or Equity need each other. Compassion gives justice a heart. It motivates justice work. And justice gives compassion hope. It overcomes the injustices that call for our compassion.

In the words of Dick Gilbert, “Justice, properly understood, is systematic, aiming at the underlying causes of social problems, not at their symptoms. Treating symptoms alone … is like putting Band-Aids on a cancer. Thus, food kitchens, however laudable, merely feed the victims of a fundamentally unjust social order instead of rooting out causes of hunger. A systematic approach challenges the underlying premises and workings of economies that produce “poverty in the midst of plenty.” (p. 39)

Or, in the words of Theodore Parker, one of the greats of our Unitarian Universalist past: “Though our mercy pulls a few out of the water; it does not stop the hole, nor light the bridge, nor warn of the peril! We need the great Charity that palliates effects of wrong, and the greater Justice which removes the cause.” (from a sermon by David Sammons)

Or, in the common example, when there are babies in the river that flows past your village, you can keep taking the babies out of the water, but you can also go upstream and find out how the babies are getting in the river in the first place—and then do something about it.

This congregation does both. It takes the babies out of the water and it seeks to fix the systems that allow the babies to get in the river in the first place. We have separate teams to address both the compassionate care and the systemic change. Both are needed. Until true justice is achieved, we will have to keep doing both.

Compassion gives Justice a heart

Compassion gives justice a heart. It motivates justice work. And justice gives compassion hope. It overcomes the injustices that call for our compassion.

Let me share with you the story of one woman whose compassion moved her to work to address the underlying causes of suffering. Margaret Sanger was the founder of Planned Parenthood. She started as a public health nurse who day after day visited scenes of suffering in which poor women were plunged into even greater despair with unwanted pregnancies.

She says, “These were not merely ‘unfortunate conditions among the poor’ such as we read about. I knew the women personally. They were living, breathing, human beings, with hopes, fears, and aspirations like my own.” Sanger told the story of Mrs. Sachs, a twenty-eight-year-old woman who had been badly hurt trying to give herself an abortion. The woman’s doctor told her that one more pregnancy could be fatal. She begged the doctor to tell her what she could do to avoid getting pregnant. The doctor said, “Tell Jake to sleep on the roof.” Mrs. Sachs begged Margaret Sanger, “Please tell me the secret, and I’ll never breathe it to a soul.” Sanger was haunted by the request, but did nothing. Three months later Mrs. Sachs was pregnant again, went into a coma and died.

Sanger left the deathbed scene and walked the streets. That night she decided that she could not go on like this, merely a witness to human suffering.

“I was resolved to seek out the root of evil, to do something to change the destiny of mothers whose miseries were vast as the sky.” The planned parenthood movement is the social action that grew out of her compassion. (p. 35-36)

Justice, Equity, and Compassion. May we affirm and promote them in our lives – in our families, in our congregation, in our wider communities, and in the world.